Stakeholder-friendly model names: Model naming conventions that give context

Analytics engineers (AEs) are constantly navigating through the names of the models in their project, so naming is important for maintainability in your project in the way you access it and work within it. By default, dbt will use your model file name as the view or table name in the database. But this means the name has a life outside of dbt and supports the many end users who will potentially never know about dbt and where this data came from, but still access the database objects in the database or business intelligence (BI) tool.

Model naming conventions are usually made by AEs, for AEs. While that’s useful for maintainability, it leaves out the people who model naming is supposed to primarily benefit: the end users. Good model naming conventions should be created with one thing in mind: Assume your end-user will have no other context than the model name. Folders, schema, and documentation can add additional context, but they may not always be present. Your model names will always be shown in the database.

In this article, we’ll take a deeper look at why model naming conventions are important from the point-of-view of the stakeholders that actually use their output. We’ll explore:

- Who those stakeholders are

- How they access your projects & what the user experience looks like

- What they are really looking for out of your model names

- Some model naming best practices you can follow to make everyone happy

Your model names and your end-user’s experience

“[Data folks], what we [create in the database]… echoes in eternity.” -Max(imus, Gladiator)

Analytics Engineers are often centrally located in the company, sandwiched between data analysts and data engineers. This means everything AEs create might be read and need to be understood by both an analytics or customer-facing team and by teams who spend most of their time in code and the database. Depending on the audience, the scope of access differs, which means the user experience and context changes. Let’s elaborate on what that experience might look like by breaking end-users into two buckets:

- Analysts / BI users

- Analytics engineers / Data engineers

The analyst’s user experience

Analysts are interfacing with data from the outside in. They are in meetings with stakeholders, clients, customers, and management within the organization. These stakeholders want clearly articulated thoughts, answers, trends, insights from the analyst that will help move the needle forward, help the business grow, increase productivity, increase profitability, etc. With these goals in mind, they must form a hypothesis and prove their point with data. They will access the data via:

- Precomputed views/tables in a BI tool

- Read-only access to the dbt Cloud IDE docs

- Full list of tables and views in their data warehouse

Precomputed views/tables in a BI tool

Here we have drag and drop functionality and a skin over top of the underlying database.schema.table where the database object is stored. The BI Tool has been configured by an Analytics Engineer or Data Engineer to automatically join datasets as you click/drag/drop fields into your exploration.

How model names can make this painful: The end users might not even know what tables the data refers to, as potentially everything is joined by the system and they don’t need to write their own queries. If model names are chosen poorly, there is a good chance that the BI layer on top of the database tables has been renamed to something more useful for the analysts. This adds an extra step of mental complexity in tracing the lineage from data model to BI.

Read only access to the dbt Cloud IDE docs

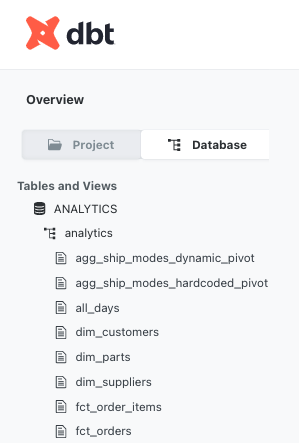

If Analysts want more context via documentation, they may traverse back to the dbt layer and check out the data models in either the context of the Project or Database. In the Project view, they will see the data models in the folder hierarchy present in your project’s repository. In the Database view you will see the output of the data models as present in your database, ie. database / schema / object.

How model names can make this painful: For the Project view, generally abstracted department or organizational structures as folder names presupposes the reader/engineer knows what is contained within the folder beforehand or what that department actually does, or promotes haphazard clicking to open folders to see what is within. Organizing the final outputs by business unit or analytics function is great for end users but doesn't accurately represent all the sources and references that had to come together to build this output, as they often live in another folder.

For the Database view, pray your team has been declaring a logical schema bucketing, or a logical model naming convention, otherwise you will have a long, alphabetized list of database objects to scroll through, where staging, intermediate, and final output models are all intermixed. Clicking into a data model and viewing the documentation is helpful, but you would need to check out the DAG to see where the model lives in the overall flow.

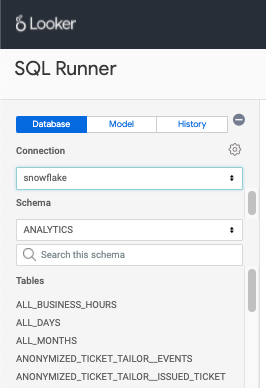

The full dropdown list in their data warehouse.

If they have access to Worksheets, SQL runner, or another way to write ad hoc sql queries, then they will have access to the data models as present in your database, ie. database / schema / object, but with less documentation attached, and more proclivity towards querying tables to check out their contents, which costs time and money.

How model names can make this painful:

Without proper naming conventions, you will encounter analytics.order, analytics.orders, analytics.orders_new and not know which one is which, so you will open up a scratch statement tab and attempt to figure out which is correct:

-- select * from analytics.order limit 10

-- select * from analytics.orders limit 10

select * from analytics.orders_new limit 10

Hopefully you get it right via sampling queries, or eventually find out there is a true source of truth defined in a totally separate area: core.dim_orders.

The problem here is the only information you can use to determine what data is within an object or the purpose of the object is within the schema and model name.

The engineer’s user experience

Analytics Engineers and Data Engineers are often the ones creating analytics code, using SQL to transform data in a way that builds trust across your team — with testing, documentation and transparency. These engineers will have additional rights and might access and interact with the project (or parts of it) from:

- Within the BI tool

- Within the data warehouse

- Within the folder structure of dbt Cloud IDE

- Within the DAG (Directed Acyclical Graph)

- Within the Pull Request (PR)

Within the BI tool

This is largely the same as the Analyst experience above, except they likely built or are aware of the database objects exposed in the BI Tool.

How model names can make this painful: There is not much worse than spending all week developing on a task, submitting Pull Requests, getting reviews from team members, and then exposing data models in the BI Tool, only to realize a better naming of the data models would make a lot more sense in the context of the BI Tool. You are then faced with a choice: rename your data model in the BI Tool (over-label as a quick fix) or go back in the stack, rename models and all dependencies, submit a new PR, get reviews, run & test to ensure your quick fix doesn’t break anything, then continue to expose your correctly named model in the BI Tool, ensuring the same name persists throughout the whole lineage (long fix).

Within the data warehouse

This is largely the same as the Analyst experience above, except they created the data models or are aware of their etymologies. They are likely more comfortable writing ad hoc queries, but also have the ability to make changes, which adds a layer of thought processing when working.

How model names can make this painful: It takes time to become a subject matter expert in the database. You will need to know which schema a subject lives in, what tables are the source of truth and/or output models, versus experiments, outdated objects, or building blocks used along the way. Working within this context, engineers know the history and company lore behind why a table was named that way or how its purpose may differ slightly from its name, but they also have the ability to make changes.

Change management is hard; how many places would you need to update, rename, re-document, and retest to fix a poor naming choice from long ago? It is a daunting position, which can create internal strife when constrained for time over whether we should continually revamp and refactor for maintainability or focus on building new models in the same pattern as before.

Within the folder structure of Cloud IDE

While developing within the IDE, you have almost the full range of information to reason about what is contained with a data model. You have a folder structure which will determine staging vs marts or any other helpful bucketing. You can see any configurations which might determine the target for your data model – database, schema, etc. You have documentation, both in line as comments and more formalized in descriptions in yml. Finally, you have the model name which should give you additional context.

How model names can make this painful: Within this context, model names do not seem as important, as they are surrounded by so much other contextual information. If you mistakenly rely on that contextual information to relay information to the end user, it will be lost when the context is removed.

Without proper naming conventions, you are missing out on a way to determine lineage. You can reason about this with folder hierarchy, or by viewing the DAG, but that’s not always possible.

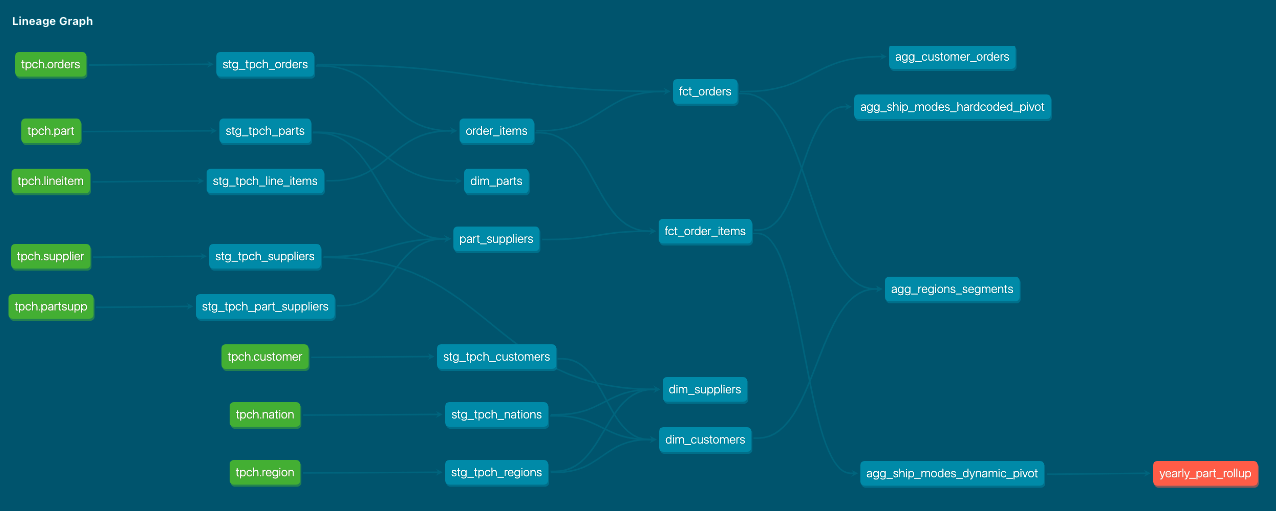

Within the DAG

By contrast, when viewing the DAG within the docs site or within the lineage tab, you get a lineage which adds more context to dependencies and directional flow. You get insight into how models are used as building blocks from left to right to transform your data from crude or normalized raw sources, into cleaned up modular derived pieces, and finally into the final outputs on the far right of the DAG, ready to be used by the analyst in infinite combinations to present it in ways to help clients, customers, and organizations make better decisions.

How model names can make this painful: The problem is that you will only see the model names (which become the nodes in the DAG), but you will not see folders, database/schema configurations, docs, etc. You can see the logical flow of data through your dbt pipeline, but without clearly defined model/node naming, the purpose of the model might be misconstrued, leading to wonky DAG pathways in the future.

Within Pull Requests

While reviewing code from someone else who is is contributing, you will see only the files that have been changed in the project’s repository.

How model names can make this painful: This will severely limit the amount of information you see, because it will be localized to the changed files. You will still see changed folders and changed model names, but lack the total project context where those are helpful. Hopefully you have a robust pull request template and traditions of linking to the task ticket and providing context to why the work was completed this way, otherwise the person reviewing your changes will not have a lot of information at hand to make clear suggestions for improvement.

Model naming conventions that make everyone happy

While each of these examples are accessing the same thing (your SQL code and the database objects it creates), the context changes depending on how you access it and none of the methods show a complete picture by themselves. The only constant between all of them is the model name, which in turn becomes the database object name and the DAG node name. This is why it is important to focus on model naming conventions, in addition to, but with less emphasis on, folder structure and schema names, because the latter two will not persist to all access points.

So what are some high level heuristics that analytics engineers can use to ensure the most information about a model’s purpose accompanies a model name?

Embed information in the name using an agreed upon pattern

Practice verbosity in a reproducible way. Extra characters in a name are free. Potential errors caused by choosing the wrong database object or mental complexity as your DAG/project expands to entropy can cost a lot.

Use a format like <type/dag_stage>_<source/topic>__<additional_context>.

type/dag_stage

Where in the DAG does this model live? This also correlates with whether this model is a modular building block or an output model for analysis. Something like stg_ or int_ is likely a cleanup or composable piece used within dbt and isn’t relevant for analysts. Something like fct_, dim_ would be an output model that will be used in the BI Tool by analysts. This should not, however, be a declaration of materialization. You should be free to change the materialization of your model without needing to change the model name.

source/topic

Gives verbose context to the content. stripe__payments tells you what source system it comes from and what are the contents of the data.

additional_context

Adding a suffix for optional transformations can add clarity. __daily or __pivoted will tell you what transformation has happened to some other dataset. This should live at the end of the model name so that they remain together in the alphabetized list (e.g. fct_paid_orders and fct_paid_orders__daily)

These 3 parts go from least granular (general) to most granular (specific) so you can scan a list of all models and see large categories at a glance and hone in on the models of interest without further context.

Coming up...

In this part of the series, we talked about why the model name is the center of understanding for the purpose and content within a model. In the in the upcoming "How We Structure Our dbt Projects" guide, you can explore how to use this naming pattern with more specific examples in different parts of your dbt DAG that cover regular use cases:

- How would you name a model that is filtered on some columns

- Do we recommend naming snapshots in a specific way

- How would we name models in the case of:

- Internet user sessions

- Orders with customers, line items and payments

- Software as a Service models with Annually Recurring Revenue/Monthly Recurring Revenue churn etc...

Comments